Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Monday, May 30, 2011

Sunday, May 29, 2011

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Friday, May 27, 2011

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

Monday, May 23, 2011

Sunday, May 22, 2011

Saturday, May 21, 2011

Friday, May 20, 2011

Thursday, May 19, 2011

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Monday, May 16, 2011

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Friday, May 13, 2011

Thursday, May 12, 2011

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Tuesday, May 10, 2011

Monday, May 9, 2011

Sunday, May 8, 2011

Saturday, May 7, 2011

Let Freedom Sing – Songs of the Civil Rights Movement

Label: Time Life Entertainment

Friday, May 6, 2011

Thursday, May 5, 2011

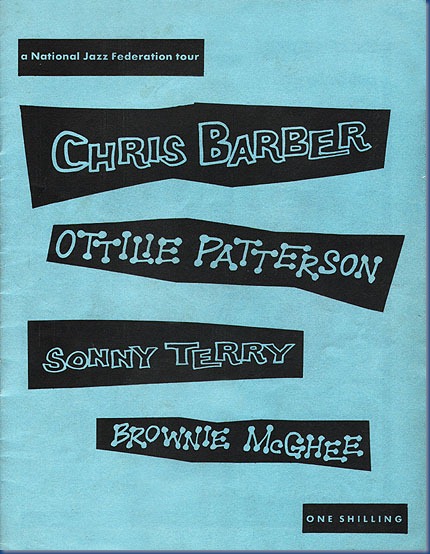

The Folk Blues and Gospel Caravan

WE HAD the "Caravan" here in England from April 29th to May 11th by courtesy of

George Wein and the Harold Davison Agency. I am now asked to write about it

retrospectively—or as my dictionary says "looking back on past events". For those who didn't see it, or didn't even hear about it (the publicity given this package was pretty bad) the line-up in order of appearance was as follows: Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee; Otis Spann, Sister Rosetta Tharpe for the first half; Cousin Joe; Blind Gary Davis and Muddy Waters for the second session. Lightnin' Hopkins was booked but fell "sick"—by all accounts the ailment was a great aversion to aeroplanes, not surprising in one so unfait as Lightnin', who has now been booked per mare for later this year. Mississippi John Hurt was also due but had a chest cold on the day of departure and as he is seventy-two years young, it was wisely decided to postpone his visit. This was a great pity but even so one couldn't help thinking that there were maybe too many artists as it was, for good as they were, one seldom saw them for quite a long enough spell. (Memo: someone must surely now bring Muddy Waters back for some club dates!) This roster of blues brilliance was further supplemented by Little Willie Smith who played drums for one number each with Sonny and Brownie, Cousin Joe and Rosetta, and Ransom Knowling, a surprise and terribly welcome bassist from the history books of blues recording, who played in the same groups. Both played full-time with Otis Spann and Muddy. Brownie played a number with Cousin Joe and Sonny duetted often for two or three numbers with Blind Gary, so everyone as you'll see, had quite a lot to do. The compere was Joe Boyd, and a

very fine job he did, while doubling as tour manager along with John Hurt's manager

Tom Hoskins, who'd come along for the trip, and who promises to bring back John with his newest "find" Robert Wilkins, now practising as a preacher down in Memphis. The

programme was a masterpiece of its kind with fine photographs and excellent notes by Paul Oliver who'd now doubtless be writing his report if he weren't working away in

West Africa. Paul's absence is regretful, as no blues writer ever brought to life a concert so vividly as he did with the "Folk Blues Festival" of last year in this magazine. I saw, heard or was present at four concerts in all, in fact the last four in a row, and the variety of things done by each artist makes writing up the events a trifle difficult. Blind Gary, for example, could be pretty erratic, as at the New Victoria second house when he played two instrumentals under great strain, then had to be led off stage by Sonny Terry in a state of near collapse, apparently quite overcome by his reception. Anyone who saw that show probably thought they had a bad deal, but to expect a genuine street singer to turn out any sort of professional performance is to destroy all the things that are good in the blues and gospel idioms. If you were lucky, and apparently you had an 80% or better chance, and saw Gary at his very fine best, as I did for 35 minutes at Brighton, then I'm sure you'd agree that Gary Davis on stage can produce the most wonderful country gospel music any concert stage is ever likely to see. His moving and beautiful rendering of Pure Religion was one of the most wonderful things I have ever witnessed; and Muddy Waters, following on, broke his usual silence to pay sincere tribute to "the great Reverend". In fact Muddy announced every number at Brighton and produced one of his best performances, including My home is in the Delta for Belgian bluesophile George Adins, a hard version of Got my Mojo working with which a pretty cold audience positively refused to associate itself, and a mean rendering of Nineteen years old which one could well imagine was sung at some silent gathering. With some of the encouragement he got last year at Croydon, Muddy I'm sure would have produced great things— as it was he seemed resolved to give 'em the straight text-book stuff they seemed to want, especially at the first New Vic show where his bottleneck rang out reminiscent of early records, and Ransom Knowling played the sort of bass that showed just why Bluebird employed him for something over two thousand titles. Perhaps Muddy's best display was the Croydon concert, where as last year the audience knew how to react, and having got past Mojo were really settling in for some great blues when the Queen rang out leaving Muddy and Co. standing around looking pretty embarrassed and not a little annoyed. Such mismanagement spoiled one of the highlights of the tour.

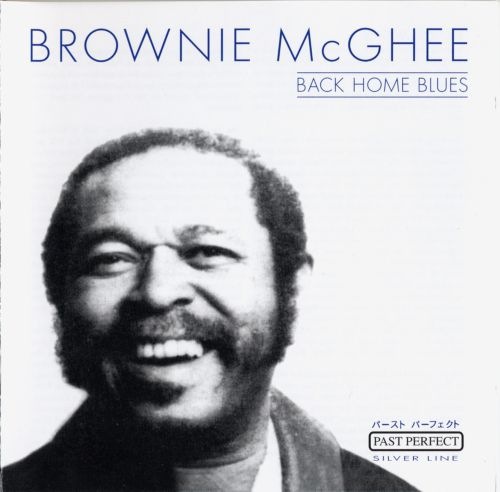

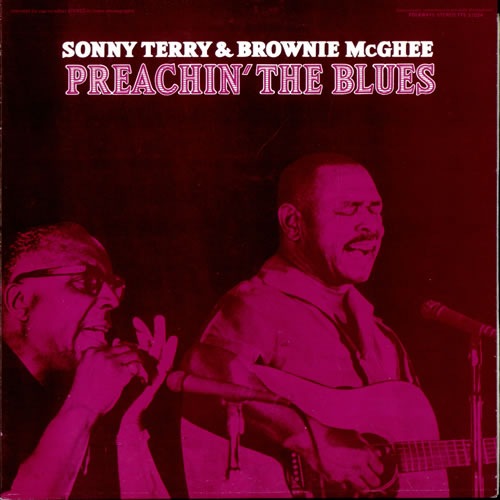

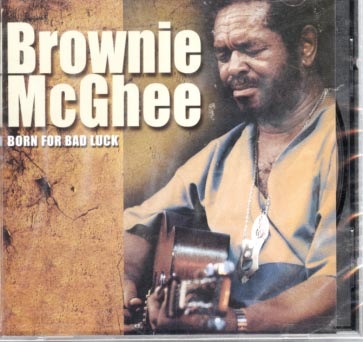

Sonny and Brownie were probably picked to open the proceedings on the strength of

their long experience, and uncanny ability to get the confidence of the spectators. Their act had the slickness that has lost a lot of their appeal on record but which never fails to enthrall live; through the four shows only Sonny's show-piece and the "walk-off" song Walk On were repeated. As expected, they had no bad times, and the splendid Key to the highway given out at Croydon only emphasised what we already knew—that these two have overcome and triumphed, but can still sing their blues with feeling and a load of talent. Certainly there will never be another pair like this, and if ever I hear another play harmonica so completely, it'll be a great day for the blues.

Otis Spann and the rhythm joined Sonny and Brownie for their last number andstayed on for Otis's spot, which usually consisted of a very jazz-flavoured instrumental and the rather unsuitable T'aint nobody's business if I do, both played with great aplomb and a wonderful left hand. Otis with better material would certainly be as big a draw as his great leader, and no doubt one day he will get to be a very popular artist indeed. The group sometimes stayed on for Sister Rosetta's act which I must confess shattered my eardrums to the extent that I could only manage one whole act. Complete with pink wig, beautiful gowns and shining new solid Gibson, reputedly setting her back 750 dollars, she was even louder than previously and no less wonderful to see. The audiences sat stupefied by this woman until she decided they should join in and clap, shout or stamp to her music. Songs like Up above my head and This train did things to these staid audiences that makes one suddenly see why such amazing things happen during similar shows at "red-hot meeting places" in Harlem and all over the States.

The second half began with Cousin Joe. Now I've never thought too much of Cousin Joe on the many records I've heard, except to admire his sly, devious or downright bawdy songs. Which just shows how wrong one can be. This we know of course from Sonny and Brownie or Muddy even, whose records in recent years have given little indication of what they can do. The mediums are worlds apart in every other sense too. But Cousin Joe was something one could not possibly have expected. Off-stage he is a very charming, quick-witted, disarming figure, with a good line in stories and a great hand at coon-can. He is pretty adept with a whiskey bottle also, but however one meets him, he has always a merry eye and a certain quiet dignity. The funniest thing I heard from him was an attempt to describe the great Pete Brown, whose proportions rather overawed Joe: "Man he was somp'n, well . . . he made that thing round his neck look like a kazoo ! Yeah he was a big guy." With suitable arm movements and a rubber face, almost anything Joe said came over in three-dimensions. But onstage he was somethin' else. Every song he chose was one of his old famous numbers, but he never made any visual impact on record.

Singing verses such as "Wouldn't give a blind sow an acorn, wouldn't give a crippled crab a crutch" and emphasising his claim by changing the second four to "No . . . blind sow an acorn, Weeell, whoo, paralysed crab a crutch", he would further state thoughtfully "Yeah, I'm a hard man", and such antics as a stuck-out tongue, rolling eyes, and a terrible chuckle brought the house down almost literally on every occasion. Showmen such as Cousin Joe are not made—he is a "natural", and though his hoarse voice and thunderous but unmusical piano-playing seem on reflection very little, he was undoubtedly, with Blind Gary, the surprise, delight and undisputed success of the show. And this was some show, even in retrospect. That more packages are even now being booked is a sign that these affairs pay both artists and promoters. With a bit more publicity the door is open for any amount of great artists— and there are plenty left yet. Even now Hooker the Great is in England, Jimmy Reed, Howlin' Wolf and Buddy Guy are coming, and the 1964 "Folk Blues Festival" is booked for the Autumn. With such activity, and such undoubted talent,

the future of the blues in Europe seems secure. SIMON A. NAPIER

(From Jazz Monthly July 1964 , pp 6-7)